As we enter our second Fashion Revolution week during the COVID-19 pandemic, we look back at how repeated lockdowns have changed the fashion industry.

With the majority of industries being hit negatively by the COVID-19 pandemic, the fashion industry has not avoided the effects of repeated lockdowns across the world. Brands that were formerly a staple of the British high street, like Debenhams and Topshop, have closed all of their stores as the way we buy our clothes has been pushed almost entirely online. Just over one year on from the start of the first lockdown in the U.K. and during Fashion Revolution Week, we wanted to reflect on how these changes have affected those working in the fashion industry. Many saw the first lockdown as an opportunity for the fashion industry to hit pause and come out the other side of it more sustainable, but are we actually any closer to this?

The totally imbalanced power structure of the fashion industry was brought into sharp focus in the first few months of the pandemic as international brands began cancelling their orders. In an ideal world, this could have at least been a sustainable choice as they knew there would be a decreased demand for their products and many would go to waste. The reality is these large brands often pay for their orders weeks or months after they’ve been sewn and at the point of cancelling these orders, garments workers had already put in many hours of work to produce them.

Big brands seemingly felt no responsibility for the workers in their supply chains as their wages and livelihoods were taken away from them. According to Clean Clothes Campaign, a global network dedicated to improving the working conditions within the fashion industry, in the first three months of the pandemic alone estimates reported that garment workers were owed ‘between $3.2 billion and $5.8 billion (USD)’ (around £2.4 to £4.6 billion) in lost wages or unfair severance pay. Through placing pressure on these brands with campaigns like #Payup much of these initial cancelled orders have been repaid, but the delay in payment has created unstable conditions for the suppliers and this money hasn’t always reached the garment workers.

When talking about the people who produce our clothes, it is easy to assume that these abuses of workers’ rights are happening in other countries as this can be where much of the media attention focuses. But the pandemic has highlighted the often ignored problems within the garment industry in the U.K. In 2018 the Financial Times reported on the illegal practices of some of the factories operating in Leicester, referring to them as the ‘dark factories’, with the average wage being reported as £4.25 and in some, it being as low as £3.

Leicester became a hot spot for Covid last summer with lockdown extended there even once other parts of the country began to open. The spread of the virus there was eventually linked back to the working practices of these factories with no social distancing measures put in place and staff being asked to carry on working even when they were sick. These actions placed pressure both on workers’ livelihoods and their lives, in January this year it was reported that women working in garment factories were one of the groups most at risk from dying from Covid.

Labour Behind the Label, a not-for-profit campaigning group, who published the report into these factories last year, found that the online fashion retailer ‘Boohoo accounted for at least 75% of clothing production in Leicester’. Scrutiny was placed on Boohoo with £1 billion being wiped off its market value overnight and online campaigns like #boycottboohoo piling pressure on the retailer through its social media channels. Boohoo has since promised to stop working with any suppliers that fall short of its code of conduct but these promises have been made before. Boohoo is just one of the thousands of fashion companies relying on an unregulated industry to make huge profits for their CEOs and shareholders.

Blame continues to be shifted from retailers to suppliers with neither taking full responsibility or genuine action, leaving garment workers still being exploited and underpaid.

With Boohoo recording pretax profits of £92.2 million in 2019-2020, many have said its successful business model has been the cause for the demise of older high street brands. In a year that’s seen Debenhams, Edinburgh Woollen Mill and Arcadia, the retail group that includes Topshop and Dorothy Perkins, go into administration it’s easy for their owners to blame the pandemic. In reality, the lack of regulation in the industry has meant that the multimillionaire owners of these companies have been able to take resources out of their businesses finances for years just to top up their own bank accounts. In 2005, Sir Phillip Green, the former owner of Arcadia, gave himself one of the largest ‘paycheques in corporate history with a £1.2 billion dividend…four times the annual profit made by Arcadia’ according to Labour Behind the Label. This huge sum was actually paid to his wife in Monaco meaning that no tax was claimed on it. Just the loss of these three companies sees almost 30,000 jobs put at risk here in the U.K. and they are yet to pay their suppliers for cancelled orders.

With little positive news coming from the large fashion retailers over the course of the pandemic, hope for a shift towards greater sustainability in the industry has come from individuals, as consumers, as home sewers, as repairers and as online activists.

Online activism is often criticised for being performative without seeing any real change but the power of so many people, and particularly for brands, so many consumers, contacting fashion brands directly via Instagram or Twitter is undeniable. The #Payup campaign forced many brands into paying for cancelled orders and #boycottboohoo forced Boohoo to review and make new policies in terms of ethical working practices. Fashion Revolution Week encourages us to contact our favourite brands to ask them #whomademyclothes to make them look into their own supply chains. The more we all try to continue this action outside of campaigning weeks or when the news is focused on other stories, the more likely it is that brands will have to actually follow through on their promises and change their behaviour.

The demand for reusable face masks when the first lockdown began to ease in the U.K. meant that many people who hadn’t touched a needle and thread in years were suddenly becoming home sewers. Blog posts teaching people how to make their own face masks from old clothes took over the crafting side of the internet, whilst sales of domestic sewing machines soared up by 127%. For many, the desire to learn new skills in lockdown added a sense of purpose to their day, in our article for Pebble magazine last April we talked about the therapeutic aspects of sewing and how helpful it can be in practising mindfulness.

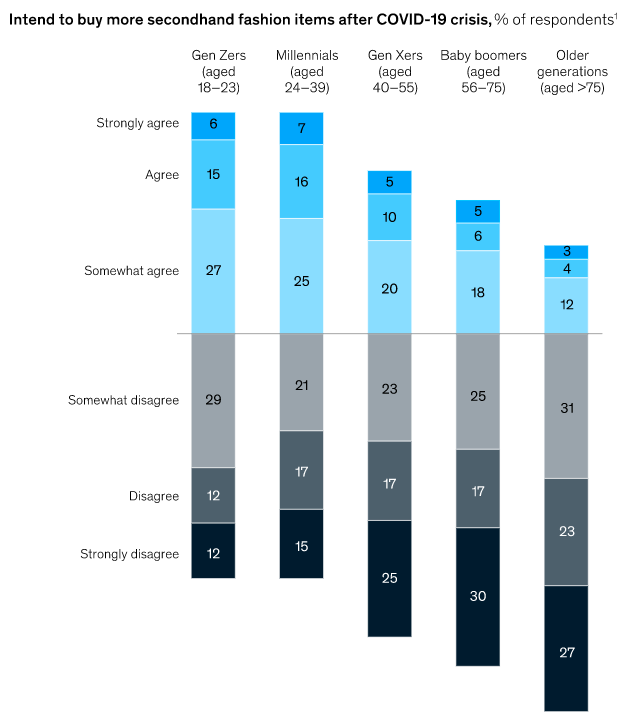

Second-hand clothing sales have also seen a huge boom, with data from eBay revealing that ‘two secondhand fashion items were sold every three seconds between January and July’ of 2020. The time to reflect on our buying decisions has allowed many people to realise how easy it is to buy quality items second-hand. Online resale marketplace Depop has also ‘seen demand for its service double during the Covid-19 pandemic’, and McKinsey’s State of Fashion report for 2021 shows that this rise in second-hand sales is being driven largely by Gen Zers (people aged 18-23) and millennials (aged 24-39), with 48% of people in these age groups surveyed stating they intend to buy more second-hand items after the COVID-19 crisis. With other data from the report suggesting that 71% of respondents ‘are planning to keep the items they already have for longer’ and another 57% are ‘willing to repair the items to prolong usage’, there is hope that this change in behaviour can’t just be called a passing trend.

A year of uncertainty has shown how fragile the business model of the fashion industry can be and in times of crisis, it is those at the bottom of the industry who pay the price. This post has only covered a small snapshot of the issues that have happened in the last year, the accounts of forced labour that have come out of Uighur highlight how long-lasting and hidden these problems can be.

Educating ourselves about them can be overwhelming but a shift in the public consciousness about the value and quality of second-hand and repaired items is undeniable and if it continues, brands will take notice. The responsibility for large scale change lies with governments and industry heads, but our choices now can help to change their behaviours and shape a fashion industry we can feel proud to support.

If you want to take part in this years Fashion Revolution Week you can find out more information about the campaign and the organisation here. Join us for our online workshops for help with your repair and sewing problems.

Want to get involved and ask your favourite brands #whomademyclothes? Follow our tips here.