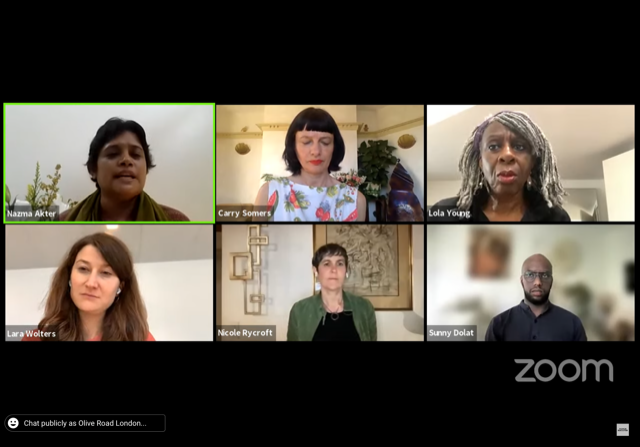

Fashion Question Time has become a key part of the Fashion Revolution Week calendar over the last few years and acts as an essential platform in bringing together activists, legislators and business owners, allowing the general public to ask them questions and hearing their ideas from inside the industry.

This years’ panel focused on ‘Rights, Relationships and Revolution’ and was made up of Nicole Rycroft, founder and executive director of Canopy, Nazma Akter, a Bangladeshi trade unionist and founder of AWAJ Foundation, Lara Wolters, a Dutch politician and member of European Parliament and Sunny Dolat, a creative director and co-founder of The Nest Collective . Chaired by Baroness Lola Young, co-chair of the UK’s Ethics and Sustainability in Fashion parliamentary group, the panel seemed to be truly representative of the different perspectives that form the fashion industry.

‘The health of the world is essential for people and future generations…Nature needs to be seen as a stakeholder’

Carry Somers

Below we go through some of the questions asked and some key takeaways from the session.

Lara Wolters and Sonny Dolat both acknowledged how climate and racial justice are so strongly connected generally, but particularly within fashion. Dolat discussed how ‘as far back as the 1950s the garment industry has relied on black and brown labour‘ and when it comes to the climate crisis, black and indigenous communities are the ones that suffer first. He also talked about how the industries desire to always find the cheapest labour meant that suppliers with bad working practices were moving between countries to set up new factories. Ethiopia is meant to be the next hotspot for the garment industry but one of the main draws here is the lack of a minimum wage.

Wolters talked about many of the ‘undesirable consequences of the fashion industry‘ and of the people affected by racial and social injustice. But she also highlights how many of these ‘oppressed people are now getting a voice’ through social media and there is a much greater awareness of the problems. At the moment there are no straightforward solutions but this pressure will force companies to start making some.

Nazma Akter felt strongly that sustainable consumption wasn’t possible under capitalism asking ‘eight years after the Rana Plaza disaster, what has changed? Nothing’.

Akter discussed how even during a strict lockdown in Bangladesh, factory owners put pressure on the government to keep factories open, particularly as lockdowns were eased in Europe and the USA. She felt there had to be a ‘fight against capitalism and neoliberalism’ in order to place the needs and rights of workers at the top of the business owners priorities.

‘There is a necessity for a fundamental rethink of how we think about business…fundamentally, it’s a question of social and racial justice’

Barroness Lola Young

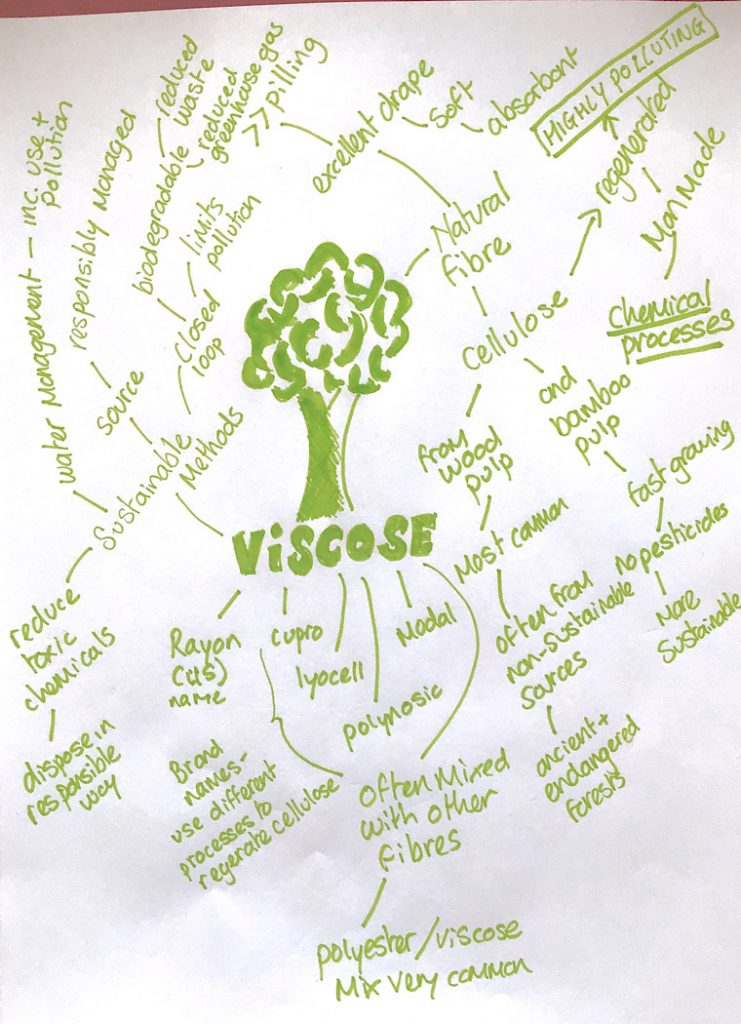

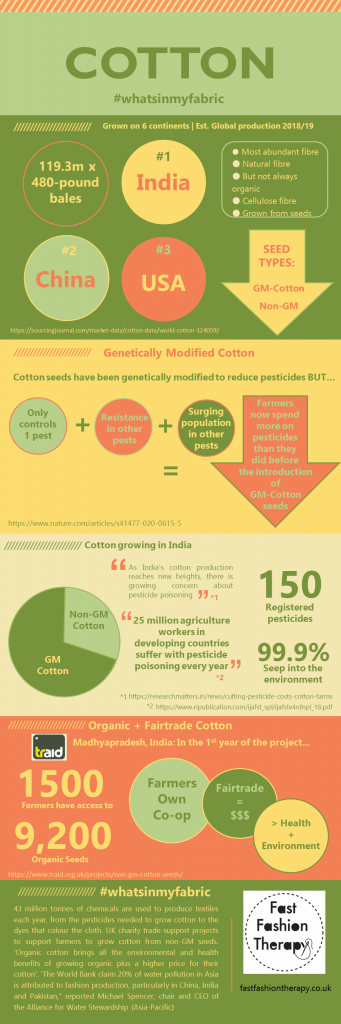

Wolters responded to this question by discussing the shocking number of chemicals used in our clothing, with around 800 of them known to interfere with hormones in both males and females. Since 1996 the EU has recognised these chemicals as hazards but she again highlighted how the interconnectedness of government and business meant it had been hard to get them banned. ‘Lobby from the industry on these chemicals has been powerful’ leaving legislators fearful that any ban would affect the EU’s trade agreement with the US. There is some hope as an EU commission is still working on banning these chemicals in products with exceptions only being allowed if their use is proven essential for society.

All the panellists felt the need for both incentives and penalties from governments in order to encourage sustainability and innovation in the fashion industry. Dolat mentioned how these are essential as ‘if governments don’t incentivise innovation then people will replicate failed models’.

Wolters discussed how attempts at voluntary schemes have not really worked, and often allowed companies to greenwash or hide bad practices more easily. Legislation needs to affect shareholders, to disincentivise CEOs from making quick decisions that affect the environment and human rights and look ‘to create a race to the top rather than a race to the bottom’. In talking about H&M’s involvement in the forced labour camps in Uighur, Wolters mentioned how initially H&M tried to do the right thing by placing pressure on China to stop this practice but the Chinese government ‘bullied’ them into staying quiet. Similar accounts came out of the US, with the US government pressuring brands to stay quiet in response to the Black Lives Matter protests.

Nicole Rycroft commented on how there isn’t actually a need to normalise these incentives as they are already normal for other ‘pernicious industries‘ with trillions of dollars given out in subsidies to the fossil fuel and farming industries. She instead questioned how we move this across to industries operating in the circular economy or with socially just practices.

‘We are not against the industry, we are against the system’

Nazma Akter

Rycroft talked about how the idea of limiting growth in production doesn’t have to be seen as going backwards and how we need to look at disrupting linear supply chains.

‘We’re smarter than using 400, 500 year old trees to make fabric and pizza boxes’

Nicole Rycroft

There is a sense of positivity when looking at the innovation she has seen in the industry in adopting rental, repair and remodelling business models and sees the brands ability to change as necessary as they won’t be ‘viable businesses in thirty years time’ when access to raw materials runs out.

‘Rights of humans and nature are inextricably bound’

Baroness Lola Young

There was optimism in Atker and Rycroft’s responses to this question with both stating it simply comes down to people’s willingness for change.

‘…if people are willing it could happen tomorrow, or it could be years and years…nothing is impossible.’

Nazma Akter

Rycroft discussed how the scientific research on the climate crisis shows it is essential that we turn our situation around in this decade but also, that ‘if Covid has shown us anything, we can literally change everything overnight if we want to’.

Orsola de Castro, co-found of Fashion Revolution, finished with a closing statement that reinforced the need for a complete reevaluation of our systems in order to evolve and asked fashion brands to see sustainability not as a business opportunity but as a moral obligation.

Key points from Fashion Question Time 2021

- Environmental and human rights need to be top of the agenda for business – respecting nature and the rights of workers should be a moral obligation, it is also the only way that industry can continue to be viable into the future. There is a necessity to work with nature to create new methods of production, to build workplaces that are safe for and respectful of their workers and to strive towards a circular economy.

- Legislation is key to genuine change – governments and businesses need to start putting the planet and people before profit. Governments need to shift subsidies from supporting damaging industries to fund those that are sustainable and ethical and to put legislation in place to give workers, consumers and citizens a voice.

- Our voices do have power – without social media, many of the accounts of oppression and abuse suffered by garment workers would not have surfaced about the fashion industry. Marginalised people and their allies now have a voice against corrupt governments and businesses and we can continue to place pressure on brands and politicians to change their behaviours.

‘There are no experts and learners in this life, we are all continuously both.’

Orsola de Castro